Autore

Indice

- Intro

- The General Function of Imagination

- The Imagination of Form, Matter and Motion

- Imagination as Poetry

- Poetic Reverie and Imaginative Creation

S&F_n. 08_2012

Abstract

Bachelard’s works on imagination have been used primarily by literary critics interested in the archetypal imagery of writers. His treatment of the imagination of matter has led to a method of classifying poets according to their favorite substances, based on a view of Bachelard as a “psychoanalyst” of the elements. But the phenomena of imagination, the images themselves, are not his fundamental concern. Bachelard’s physics and chemistry of imagination also imply a metaphysics. Definition of the contents and function of imagination illustrating a philosophy of imagination in itself is the purpose of the present essay.

- Intro

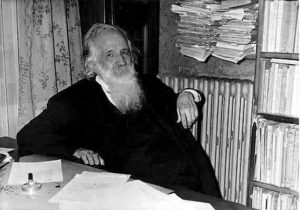

The academic career of Gaston Bachelard (1884-1962) was devoted to epistemology and the history and philosophy of science[1]. A militant rationalist and materialist concerning science, Bachelard also indulged his rich imagination in a series of studies on imagination, from The Psychoanalysis of Fire (1938) to The Poetics of Reverie (1960)[2].

These essays examine the images of various writers whose works provide the subject matter for Bachelard’s own theorizing on imagination. His working method was one of empathy with the text, identification with the supposed inner impulses of the writer. Bachelard’s style is correspondingly subjective and personal, with theoretical formulations interspersed with his own play. He often uses technical terminology from literature, phenomenology, metaphysics, esthetics, etc., in a novel way, reinterpreting their accepted meanings in terms of his present perspective. The multiplicity of perspectives, reinforced by an exceptional lexical luxuriousness, has made Bachelard’s thought on imagination appear more obscure than necessary. However, underlying this protean aspect of his writing is a consistent conceptual framework, a philosophy of imagination.

Bachelard’s works on imagination have been used primarily by literary critics interested in the archetypal imagery of writers. His treatment of the imagination of matter has led to a method of classifying poets according to their favorite substances, based on a view of Bachelard as a “psychoanalyst” of the elements[3].

But the phenomena of imagination, the images themselves, are not his fundamental concern. Bachelard’s physics and chemistry of imagination also imply a metaphysics. Definition of the contents and function of imagination illustrating a philosophy of imagination in itself is the purpose of the present essay. Bachelard studies the creative aspects of imagination not only phenomenologically, but as constituting an ontology.

Ultimately, Bachelard’s study of imagination in its creative purity has a profound moral commitment, «to reestablish imagination in its living role as the guide of human life» (Air, p. 209). This ethic of free imagination underlies Bachelard’s definition of imagination as human transcendence.

- The General Function of Imagination

Bachelard’s general concept of imagination firmly establishes it as a creative faculty of the mind as over against a simple reproduction of perception. Traditionally imagination is thought of as the faculty of forming images. For Bachelard, however, imagination «is rather the faculty of deforming images provided by perception; it is above all the faculty of liberating us from first images [here, representations in perception], of changing images» (ibid., p. 7). This freedom from a mental imitation of reality – e.g., sight – Bachelard calls the “function of the unreal,” the imaginative force which enables man to create new images instead of adjusting to reality as given. Man’s capacity freely to exercise his imagination is, for Bachelard, the basic measure of his mental health[4].

The change and deformation of images result from an action intrinsic to imagination: «Imagination is the very force of psychic production, more than will or the élan vital» (Feu, p. 149). Imagination is manifested as an aspiration toward new images; it is a force of becoming for the human mind. Bachelard thus uses the Kantian distinction between productive and reproductive imagination to establish an elementary ontology implied by the very direction of imaginative activity, that of constantly going beyond one’s present being. Imagination is, on the level of its images, a force of transcendence[5].

For example, imagination can be described as excess in all modes of awareness, from images to ideas, and even to scientific theories: «the sign of too much is the very seal of the imaginative» (Volonté, p. 26). Imagination tends to shift constantly between the cosmos and the microcosm, project the large on the small and the small on the large, to speed up normal velocities – generally to dispel our inert habits of experience and knowledge[6]. This quality of increase is the continuity of creative power, which Bachelard also calls “the poetic”: «the poetic function is to give a new form to the world which poetically exists only if it is unceasingly reimagined» (Eau, p. 81). Man’s creation of new images, then, is derived from this psychic power of constant becoming, described, by Bachelard, as imagination.

Finally, the autonomy of imagination is the precondition of its creativity. His philosophy of imagination derives its rules from the primary functions of imagination itself[7]: «Imagination is a prime force. It should originate in the solitude of the imagining being» (Air, p. 204). Autonomy as solitude refers to the necessary isolation of the imagining consciousness from external perceptions. Considered in its full potential of freedom, «imagination is never wrong, since imagination does not have to confront an image with objective reality» (Espace, p. 144). We thus have an idealist ontology based on its own context of imaginative activity. The degree of creativity of imagination (as opposed to simple perception or memory) is often determined by the extent of free elaboration of images. For example, «with an “exaggerated” image, we are sure to be on the axis of an autonomous imagination» (ibid., p. 149). From Bachelard’s point of view, then, the images produced by imagination must be different from perceptual reality. The autonomy of imagination is thus a view of imagination as other than, ontologically opposed to perception, though carrying its own ontological validity.

Objective and Affective Knowledge. Bachelard, whose professional recognition lay in the history of science and epistemology, clearly distinguishes between the objective knowledge of science and the emotional reactions which subvert empirical descriptions[8]. Observation colored by emotion is a turning inward toward intimate experience, a separation from outside perception: «what is purely artificial for objective knowledge can be profoundly active and real for unconscious reveries. Dream is stronger than experience» (Feu, p. 40). This freedom of personal emotions in observation is a corollary of the autonomy of imagination: «the less one knows the more one names» (ibid., p. 129)[9]. Affectivity is a commitment to the pleasures of personal imagination.

Bachelard calls this affective distortion of reality “valorization”, a form of knowledge which transforms its object: «It is not knowledge of the real which makes us passionately love it. It is rather feeling which is the primary and fundamental value. One starts by loving nature without knowing it, by seeing it well, while actualizing in things a love which is grounded elsewhere. Then, one seeks it in detail because one loves it on the whole, without knowing why» (Eau, p. 155). The desire which precedes perception is here a commitment to understanding. Besides enriching perception, valorization also has a creative component: «Imagination does not seek a diagram for summarizing knowledge. Imagination searches a pretext for multiplying images; and as soon as it becomes interested in an image, it overrates its value» (Espace, p. 143)[10]. Valorization thus asserts the creativity of the individual as over against objective evaluation. Here is «one of the great [ontological] principles of the Imaginative: valorization decides being» (Air, p. 90).

Psychic Determinants of Imagination. Imaginative freedom from perception, however, is not entirely autonomous, but relatively determined by the structure of the human psyche. Bachelard’s so-called psychoanalytical approach to imagination–his descriptions of images in terms of complexes and archetypes – has been overemphasized to the detriment of his more fundamental phenomenological method, the perspective which considers rather the dynamism itself, not the antecedent causality, of imagination. The psychic structure of imaginative experience, which limits it, is simply the “form” of a creativity which is essentially free force.

Bachelard’s view of the psyche, as was suggested by the fact of affective valorization of knowledge, takes into account the influence of the “unconscious” of classical psychoanalysis, which he describes through the metaphor of the tree:

The dream has a taproot which descends into the great and simple subconscious of primitive infantile life. Dream also possesses an entire network of lateral roots which live in a more superficial layer. The conscious and the unconscious intermingle in this region, the region we have principally studied in our works on imagination. However, the deep zone is always active. The first centers of interest are constituted by an organic interest (Eau, pp. 158-159).

The “taproot” of dream, of imagination as subconscious causality, draws on the great archetypes which structure fundamental human experiences. The “lateral roots” function in a median zone where primitive instincts may distort clear thought, e.g., affective perception, or reverie. In this intermediary zone, imagination confronts consciousness. Fundamentally, from this deterministic perspective, the primary organic needs of infancy could encourage the adhesion of affectivity to certain life experiences[11].

Imagination, however, is more than emotional perception directed by subconscious needs and complexes. Imagination is a synthesizer of all modes of consciousness: «Imagination has the integrating powers of the tree. It is root and branch. It lives between earth and sky. Imagination lives in the earth and in the wind. The imagined tree is imperceptibly the cosmological tree, the tree which summarizes a universe, which makes a universe» (Repos, pp. 299-300). The two main functions of imagination are synthetic (“summarizes a universe”) and creative (“makes a universe”). Ultimately the psychological determinants of imagination are transcended by its total function as origin of reality.

Bachelard’s psychoanalysis of imagination is therefore one possible perspective. From this developmental standpoint, the median zone of the psyche is the one most susceptible to the accidents of experience. Certain “primitive images” cause “imaginative polarizations”, the preference of imagination for particular types of images, e.g., images of fluidity. Psychology as a reductionism would thus seek the trauma which the image clusters would suggest. These clusters are formed by «sights and impressions which have, suddenly, given an interest to an object which usually has none. All imagination converges on that valorized image» (Feu, p. 149). Traumatic emotion is also at the origin of memory, for Bachelard: «True images are engravings. Imagination engraves them in our memory. They elaborate lived memories, displace lived memories, to become memories of imagination» (Espace, p. 46). To be utilized, in fact, such valorized memories must be reimagined, infused with fresh affectivity: «We have microfilms in our memory which can be read only by the living light of imagination» (ibid., p. 161). Emotional value is thus the prime component of imaginative perception which itself underlies the synthesizing function of imagination[12].

The deepest psychic structures of imagination are the archetypes. Bachelard specifically organizes much of his research around the four imaginative elements air, water, earth and fire – «in order to study the determinism of the imagination» (Volonté, p. 211). These imaginative elements «have idealistic laws as certain as experimental laws» (Air, pp. 14-15). Bachelard also calls the four elements “the hormones of imagination”: «They execute the great syntheses which give a little regularity to the imaginative. In particular, imaginative air is the hormone which makes us grow psychically» (ibid., p. 19). It is only later that “conditioned reflexes” develop from the «fathomless oneiric foundation which the personal past paints with particular colors» (Espace, p. 47). Bachelard is using these technical terms from physiology and psychology to show the relative determinism which life exercises on free imagination[13].

Bachelard relates the unconscious which all humans share to the Jungian notion of the archetype:

While studying prime images, one can develop for each of them almost all the problems of a metaphysics of the imagination. In this respect, the image of the root is particularly apt. It corresponds in the Jungian sense to an archetype buried in the unconscious of all races and it also has, in the clearest part of the mind up to the level of abstract thought, a power of multiple metaphors, always simple, always understood. The most realistic image and the freest metaphors thus cross all regions of the psychic life (Repos, p. 290).

The tree metaphor again expresses the influence of the imaginative – here of archetypal structures – on all levels of consciousness. This «absolute unconscious» (ibid., p. 6) is another case of imagination preceding perception.

Indeed, the archetypes even precede the creation of images within imagination: «Imagined images are sublimations of archetypes rather than reproductions of reality. And as sublimation is the most normal dynamism of the psyche, we can show how images come out of the human foundation itself» (Volonté, p. 4). The basic notion revealed by the archetypal structure of the collective unconscious, it must be emphasized, is not one of formal determinism but of process, the fundamentally dynamic characteristic of imagination, e.g., sublimation as a transcendence of rigid psychological complexes. That imagination is force is shown when the archetypes are viewed as a «symbolic force which exists before images». To take one example, «in the unconscious, all diverse impressions of lightness, vivacity, youth, purity, sweetness, have already exchanged their symbolic value. Afterwards, the wing merely gives a name to the symbol, and the bird finally comes to give being to the symbol» (Air, p. 83). Archetypes may precede perception and expression. However, they are simply activated, not created, by the will to express. Becoming as force precedes being as image. The psychic structures in which imaginative creativity is embodied all express the same force.

Imagination as Will. A special form of desire motivates, and indeed activates, our imaginative powers. To be free and creative as imagination is to will such freedom: «Imagination and Will are two aspects of the same profound force. He who knows how to wish can imagine. To the imagination which illumines the will is united a will to imagine, to live what one imagines» (ibid., p. 130). Bachelard’s philosophy of imagination seeks «the same profound force» of which human will and imagination are the two most primitive differentiations. He relates this force to a specifically spiritual power. Just as archetypal images incarnate the psyche’s need for expression, poems illustrate an analogous intentionality: «Only poems can bring to light the hidden forces of the spiritual life. Poems are, in the Schopenhaurian sense images have an aspect of spiritual process» (ibid., p. 52). The poem represents the form (“the phenomenon”) of «the hidden forces of the spiritual life», just as all images produced by imagination manifest man’s need to create his own world of being. The spirituality of imagination as will is man’s inherent quest for transcendence through creativity[14].

A philosophy of human transcendence overrules the reductionism of utilitarian psychology which seeks reality as it is. Bachelard affirms that «man is a creation of desire, not a creation of need» (Feu, p. 34). Imagination does not need to adjust to reality, but surpasses it; imagination changes reality, produces, creates a higher reality, itself perceived as reality. Finally negating psychological reductionism, Bachelard characterizes poetic expression as «a sphere of pure sublimation, a sublimation which sublimates nothing» (Espace, p. 12). Here Bachelard underlines the ontological intrinsicality of poetic expression. Considering the created image as mere phenomenon, Bachelard affirms the essential purity of imagination as free force[15]. Desire is inseparable from the surging poetic image: will is fused with imagination in an absolute affirmation of the human spirit.

Projection and Esthetic Will. Bachelard explores more fully the relation of imagination to the objective world in the psychological process of projection. A specific case of projection, valorization of objective or empirical reality is a perceptual manifestation of imagination as will. Practiced unwittingly by the alchemists, «far from being a description of objective phenomena, it is an attempt at inscribing human love in the heart of things» (Feu, p. 87). Beauty is born in this imaginative transcendence of the objective, the neutral. One can consequently discern the character of a poetic temperament by its choice of images, since, from the point of view of perception, «imagination is nothing but the subject conveyed into things» (Volonté, p. 165). In its most general sense, imagination as projection is a humanization of objective reality[16].

The element of intimate adherence to and love of an object introduces the most essentially human mode of imaginative projection: its expression as esthetic will. This will to beautify an object of perception reflects the general tendency of imagination to surpass given reality by valorizing, by poetizing it:

In order to hear the beings of infinite space, one must silence all earthly sounds. Then, one understands that, in us, contemplation is an essentially creative power. One feels the birth of a will to contemplate which soon becomes a will to aid the movement of that which is contemplated. Will and Representation are no longer two rival powers as in Schopenhauer’s philosophy. Poetry is truly the pancalist activity of the Will[17]. It expresses the will to beauty. All deep contemplation is necessarily, naturally, a hymn. This hymn functions to surpass the real, to project a sonorous world beyond the mute world. The Schopenhauerian theory of poetry depends too much on a theory of poetry which [simply] evokes natural beauties. In point of fact, the poem is not a translation of an immobile and mute beauty, it is a specific action (Air, p. 61).

Like most activities of truly creative will, this celebration of man’s energy germinates in solitude. However, contemplation does reach toward the objective world («aid the movement of that which is contemplated») as dynamic imagination, although it transcends it in an act of creation. («This hymn functions to surpass the real»). Esthetic will manifests in this way the essential function of imagination as movement and creativity. The beauty which esthetic will actualizes in the world goes beyond a description, evocation or translation of one reality into language as reproductive imagination. Esthetic contemplation is essentially creative, vitalizing the beauty of the mute world[18].

Imaginative Reciprocity. The most profound experience with the objective world in Bachelard’s philosophy of imagination is a mutuality of experience between spectator and spectacle within true imaginative contemplation of nature. This process of reciprocity is somewhat akin to the “pathetic fallacy” of Romanticism, where the landscape becomes a partner with the poet in expressing his intimate emotions. Bachelard, however, goes beyond simple projection to endow nature itself with will:

The magnetism of contemplation is a category of will. Contemplating is not opposed to will, it follows another branch of will, it is a participation in the will to beauty which is an element of the general will. A doctrine of active imagination joins the phenomenon of beauty to the will of vision. Nature forces us to contemplation. An endless exchange is produced between the vision and the visible. Everything that makes us look looks (Eau, p. 44).

Just as the «spiritual process or force» of imagination underlies all its phenomena, so «the general will» of nature is differentiated into a solicitation of man’s attention in esthetic contemplation. Bachelard’s concept of imaginative reciprocity accounts for this «magnetism of contemplation» which joins nature and man in a common consciousness[19].

Bachelard describes this exchange of perception using the Scholastic or Spinozistic distinction between natura naturata, representing an inert, created reality, and the dynamically creative natura naturans which embodies an immanent force:

Contemplation as well induces a will. Man wants to see. Seeing is a direct need. Curiosity makes the human mind dynamic. But in nature itself, it seems that forces of vision are active. Intercourse between contemplated nature and contemplative nature are close and reciprocal. Imaginative nature actualizes the unity of natura naturans and natura naturata. When a poet lives his dream and poetic creations, he actualizes this natural unity. It then seems that contemplated nature aids contemplation, that is, it already contains the means of contemplation. Numerous poets have felt this pancalist union of the visible and the vision; they have lived it without defining it. It is an elementary law of imagination (ibid., pp. 41-42).

Bachelard’s concept of reciprocity is based on a view of man and nature as essentially identical in terms of will («the unity of natura naturans and natura naturata this natural unity»). Hence nature acted upon (natura naturata) by imagination, despite its passivity, contains the seeds of subjectivity. That is to say, natura naturata is natura naturans potentially: imagination actualizes this potentiality by uniting natura naturata out-there to natura naturans in its full intrinsicality as creative will. Imagination has again shown its autonomy by its own powers of actualization: «To our mind, imagining humanity is a beyond of natura naturans» (ibid., pp. 14-15), even though Bachelard attaches reciprocity to the phenomena of “the general will”. Human imagination acts as a force of transcendence fulfilling the immanence of the imagined or contemplated object: «In the domain of imagination, a transcendence is joined to every immanence» (Air, p. 12). Humanity thus stands above nature by its capacity to bring passive nature up to man’s own level of creativity and beauty. Man initiates and realizes «the immanence of the imaginative in the real, the continuous path from the real to the imaginative» (ibid., p. 11). Finalizing our contrast between imagination as reproduction or as creation, all phenomena are transcended, for they are simply derived from imagination itself as general creative activity.

- The Imagination of Form, Matter and Motion

The interaction of imaginative consciousness with the world of substances, of matter, specifies the general laws of imagination just described. Bachelard considers the imagination of form, the perception of surfaces, as inferior to the imagination of matter which penetrates the depth of a substance to live the values of the inside. The perspective of the imagination of motion, dynamic imagination, however, is simpler and more general, underlying them both. Dynamic imagination manifests the primitive, immortal force of psychic becoming, imagination itself as force and creativity[20].

Form and Matter. The dialectic of surface-depth describes the opposition between the imagination of form and of substance. For Bachelard, form operates on the axis of surface values, e.g., color, the picturesque, the unexpected, constant variety. Depth, on the contrary, the inside volume of a substance, seeks the permanent, the eternal. This is the realm of matter, as Bachelard says, «where form is sunk into substance, where form is internal» (Eau, pp. 1-2). For imagination, then, the true experience of matter confronts the inwardness of substances. «For the imagination of matter, every phenomenology reveals an ontology, every phenomenon has its substance» (Volonté, p. 236). The significant valorization of substances works in their depth, not on their surface.

An application in the realm of esthetics of the ontological depth of matter is the necessity for an «equilibrium between experiences and sights. The rare books on esthetics which envisage concrete beauty, the beauty of substances, often touch only lightly the problem of the imagination of matter» (Eau, p. 21). Form is static, finished, according to Bachelard: «It is contrary to its being that a form be transformed» (ibid., p. 183). The basic distinction between the imagination of form and of matter, then, is one between the perception of what is and of creativity:

In fact, the imagination of matter is, as it were, always in act. It cannot be satisfied with the finished work. Imagination of forms reposes in its end. Once realized, the form is rich with such objective values, so socially exchangeable, that the drama of valorization is relaxed. On the contrary, the dream of molding guards its possibilities. This dream underlies the work of the sculptor (Volonté, p. 101).

Form, then, is associated with clear sight and objective agreement on static surfaces. However, it is the constant activity of imagination – its essence as force – which characterizes the imagination of matter as literally a more “profound” experience of personal creation[21].

Depth and Intimate Experience. The personal aspect of the imagination of matter is ‘this “deepening” of awareness, reciprocal as is all complete imaginative perception. Esthetic reciprocity is part of the general depth of imagination: «the material image surpasses the toward the intimacy of the acting subject and within the substantial interior of the inert object encountered by perception» (ibid., p. 32). This emotional experience of the interior of substance is another form of the valorization which is the hallmark of affective perception. Matter contains «intimate beauty an affective space hidden in the interior of things» (ibid., p. 9), because of this imaginative force of projection. Introspection through the imagination of the depth of an object is based on the function of matter as an objective symbol of human emotions: «every substance intimately dreamed brings us back to our unconscious intimacy» (ibid., p. 333).

Closer to our hidden subjectivity, the «individualizing power» (Eau, p. 3) of matter also contributes to the unity of imaginative action. A valorized substance becomes the «image commentary of our organic [or intimate] life» (Repos, p. 67) by integrating the basic values which are dispersed in various forms: «When a reverie or dream is absorbed in a substance, the entire being receives a strange permanence. The dream falls asleep. The dream is stabilized. It tends to participate in the slow and monotonous life of an element. Having found its element, it melts all its images there. The dream is materialized» (Eau, p. 123). The images of a poet are his imagination objectified[22]. This integrating function of matter, it must be noted, is not free dynamic process. While deepening our inner awareness, the imagination of matter produces «a repose of being, a rooted repose, a repose that has intensity and not only the external immobility of inert objects» (Repos, p. 5)[23].

Will and the Imagination of Matter. By considering the imagination of matter from the perspective of creative will we see its more positive power. Matter supplies the «images [which] are necessary for the virtualities of our soul to be distinguished and developed» (Volonté, p. 357); it presents a challenge, a barrier, to free imagination. In the resistance of matter to our personal forces we live the true synthesis of will and imagination. Through the object’s intentional resistance, a reciprocal energy is produced by the will’s encounter with matter: «Matter is our energetic mirror; it is a mirror which focuses our powers in illumining them with imaginative joys» (ibid., p. 23). Consequently, the «dualism of subject and object is presented at its truest equilibrium; in other words, in the realm of imagination, one can say as well that real resistance stimulates dynamic reveries or that dynamic reveries will awaken a resistance dormant in the depth of matter» (ibid., p. 24). This is another case of the union of natura naturata and natura naturans in a reciprocal exercise of imaginative power. Matter, confronted by will, energizes our whole being[24].

Will thus requires imagination to remain dynamic. The principle of unity between the imagination of matter and of motion is the imaginative fact that «none of the four elements is imagined in its inertia; on the contrary, each element is imagined in its special dynamism; it is the first of a series which illustrates it» (Air, p. 15). The imagination of the interior of a substance which is at the same time the exercise of one’s intimacy is, from the perspective of dynamic imagination, both a becoming of the person and of the substance. An exact reciprocity joins the moved and the mover, moving body and motor, thrust and aspiration, to produce images of living duration. Bachelard finally emphasizes the priority of dynamic imagination: «The manner in which one imagines is often more instructive than what one imagines» (Feu, p. 54). Having examined the imagination of form and of matter, we see again that imagination is essentially action: «It is the movement, more than the substance, which is immortal in us» (Air, p. 58).

The basic ontology of imagination may thus be described: «things are not what they are, they are what they become» (Eau, p. 66). Imagination is function rather than form, movement itself rather than representation. For example, «in the order of dynamic imagination, all forms are furnished with movement: one cannot imagine a sphere without having it turn, an arrow without having it fly, a woman without having her smile» (Air, p. 58). The general phenomenon of valorization, which underlies imagination’s commitment to objects, is also derived from dynamic imagination: «If one considers that a value is essentially valorization, thus change of values, one realizes that images of dynamic values are the origin of all valorization» (ibid., p. 295). In the meeting of imagination and matter, the psyche becomes animated, amplified by its imaginative faculty of becoming.

Bachelard indicates that, like the primacy of archetypal structures over the accidents of individual experience, dynamic imagination is a fundamental structure of human nature. Here, the spiritual function of transcendence precedes its particular phenomenon of human love: «Before social metaphors, the dynamic image is revealed as a prime psychic value. Love of mankind, in putting us above our being, brings a mere additional aid to a being which ceaselessly lives above his being, at the summits of being» (ibid., p. 53). The contents of our being, our existence, are simply derived («a mere additional aid») from the essential quality of man which is to constantly seek transcendence of himself («a being which ceaselessly lives above his being»). Dynamic imagination is therefore the primitive force which animates the psyche and nourishes its fundamental power of transcendence[25].

- Imagination as Poetry

The data on which Bachelard founds his philosophy of imagination are words. For Bachelard, literature is the highest and broadest expression of man’s creativity. The potentials of all artistic media are subsumed under man’s linguistic function; it is a solid form of the “function of the unreal”: «By the expedient of literary imagination, all the arts are ours. A beautiful adjective well placed, well lighted, ringing in perfect vocalic harmony, and behold a substance. A stroke of style, behold a character, a man» (Volonté, p. 95). This creative autonomy of language derives from imagination’s freedom. Language «forms the temporal fabric of spirituality and consequently is freed from reality» (Air, p. 8), just as the dynamic imagination of matter is founded upon the function of imagination as psychic becoming, constant transcendence of what is. The domain of human creativity, as distinguished from the pure spirituality of imagination in itself, lies in its temporality. Human creativity is the spiritual realm which is in man’s grasp: «Imagination temporalized by the word seems to us, in effect, to be the humanizing faculty par excellence» (ibid., p. 20). An examination of verbal imagination should thus describe a philosophy of human creativity seeking full exercise of its essential spirituality[26].

The Will to Expression. The priority of will as the dynamic force of creative imagination applies also to verbal expression, the highest form of human will. Bachelard judges will’s priority by considering consciousness in the silence which precedes expression

and returning to the will to speak in its nascent state, in its first vocality, entirely virtual, blank. Silent reason and mute declamation appear as the first factors of human becoming. Before all action, man needs to utter himself to himself, in the silence of his being, that which he wishes to become; he needs to prove and to sing his own becoming to himself (ibid., p. 278).

Bachelard is describing, in the language of a phenomenology of poetic creation, the need for creative will to precede action, the solitude which autonomous imagination ultimately requires. By studying the psyche before expression, Bachelard seizes the purity of the will to expression.

Verbal expression itself is, for Bachelard, the most accurate indication of the workings of will and imagination, the two most fundamental powers of human spirituality:

In the entire realm of will, nowhere is the path shorter from will to its phenomenon. Will, if seized in the act of utterance, appears in its unconditioned being. It is there that one can say that will wants the image or that imagination imagines will. There is synthesis of the word which commands and the word which imagines. Through the word, imagination commands and will imagines (ibid., p. 276).

The phenomena of will and imagination – e.g., images, thoughts, words – embody pure will or spirituality, hence when «imagination imagines will» it concretizes its force in images just as when «will wants the image» it seeks expression, an objective form, temporality. The will to expression, by which Bachelard characterizes true poetic creation, is the purest phenomenon of self-transcendence through artistic creation, the creative intentionality of imagination.

Language itself is structured according to its relative purity of spiritual function. The aspect of language determined by traditional meanings and psychological connotations corresponds to the archetypes which guide human thought: «The isolated dreamer keeps in particular oneiric values attached to language; he retains the primary poetry of his race. The words he applies to things poetize them, spiritually valorize them in a direction which cannot entirely escape traditions» (Eau, p. 182). The conventional structure of language (grammatical, semantic, rhetorical) can inhibit free poetic creation, hence the destruction of literary language and art forms which was the purpose of the original dada revolution. For Bachelard, true poetic expression liberates us from the artificial norms of society and objective thought while at the same time returning us to the deepest origins of psychic structure. In the end, however, the spiritual principle of poetry asserts itself. Poetic expression, though it may be compromised by psychological needs and linguistic conventions, is essentially an act of autonomous creativity[27].

Speaking and Writing. Examination of the spiritual force of imagination in grips with expression in speaking and writing will give us an insight into man’s creative possibilities. Bachelard stresses that «an uttered word – or even simply a word of which pronunciation is imagined – is an actualization of the entire being» (Repos, p. 68). Speech as a mode of actualization, of the objectification of spirit as sound, is the movement of imagination itself from purely virtual intentionality to concrete creation. It is man’s creation of a new reality which is the ontological dimension of speech.

Like the general forces of esthetic projection, speaking imagination also animates nature which, in turn, participates in a higher level of imaginative being:

Images are born directly from the murmured and insinuating voice. If one gives its true place to the Word creator of poetry, if one realizes that poetry creates a psyche which then creates images, the traditional diagram will be enlarged by two terms: spoken nature awakens natura naturans which produces natura naturata – to which one listens in speaking nature. Yes, as so many poets have said, nature speaks for those who listen to it. Everything speaks in the universe, but it is man, the great speaker, who says the first words (Air, p.116).

The priority of imaginative will is manifested by the function of poetic utterance (“spoken nature”) which transfers the inner experience of dialogue with its object to the outside world. Then the creative, expressive intrinsicality of nature as natura naturans produces a higher reality (an imaginative natura naturata, if you will) which is then perceived. Spoken creation carries imaginative reciprocity to a higher level of creation, where man is seen as the absolute master, the first breath, of genesis. The primacy of human creativity is the foundation of the autonomy of imagination in Bachelard’s philosophy.

Writing imagination is related to speaking imagination as the imagination of matter is to dynamic imagination. Without the vital breath of implicit or explicit speech, words remain hollow and static. Writing itself provides the cohesion necessary to psychic dynamism – as over against complete dispersion into pure free imagination (e.g., aerial imagination without aerial substance). The literary reverie, in particular, is a «strange reverie which writes itself, which coordinates itself while writing itself; it systematically surpasses its initial dream, but remains faithful to elementary oneiric realities» (Eau, p. 27). These “elementary oneiric realities” are the archetypes which relate pure transcendence, the intentionality of imagination, to the structure of human life. The coherence which writing gives to the surpassing activity of poetic expression is a new formulation of mankind.

The key to this deepening of human awareness through writing is its temporality. The separation of writing awareness from its preconscious antecedents leaves free moments of choice between will and expression: «the written word has an immense advantage over the spoken word in evoking abstract echos where thoughts and dreams reverberate. The stated word requires too much force, demands too much presence, it does not leave us the total mastery of our slowness» (Air, p. 285). This median zone where the unconscious mixes with rational consciousness is the domain of creative freedom, for there is where imagination colors or structures our responses to reality. Our awareness of these levels of consciousness as such is the freedom of man as creator in control of his creation.

From the perspective of written poetry, the moment preceding expression is one of virtual will:

Then poetry is truly the first phenomenon of silence. It lets live, under images, the attentive silence. It constructs the poem on the silent time, on a time which nothing torments, nothing rushes, nothing commands, on a time ready for all spiritualities, on the time of our freedom. How poor is living duration compared with durations created in poems! Poem: beautiful temporal object which creates its own measure (ibid., p. 282).

In its pure intentionality, imagination is a phenomenon of silence, “the attentive silence” behind which lurks self-consciousness. Imagination is freest before expression; and the slowness of writing preserves this spiritual freedom within living duration. Given the relative autonomy of the word in poetic creation, the written poem “creates its own measure” in that its temporality is verbalized spirituality, not the semantic negation of imagination as freedom.

It is through the written word that we experience in depth all the potentialities of language: «Pen in hand, one has some chance of effacing the unjust privilege of sounds; one learns to relive the largest of integrations, that of dreaming and meaning, while leaving dream the time to find its sign, slowly to form its meaning» (ibid., p. 283). The word is both a sign of an unconscious dream, an exteriorization of will as poetry, and the symbol of an abstract concept recognized by linguistic convention. Literary language exploits all the functions of the word as tool of reality or as origin of a new consciousness. Bachelard’s study of the metaphor is a polemical attack against an exclusively intellectual interpretation of poetic images in favor of a more spiritual view of their function as phenomena of creative will. His phenomenological study of the metaphor as poetic image is aimed at explaining its creative power[28].

Metaphor and Poetic Image. Bachelard clearly distinguishes between the function of the conventional literary metaphor and the pure poetic image in order to illustrate –the exclusion between reason and imagination. He exaggerates the intellectual structure of the metaphor as an equation (or comparison) between sign and signified in order to combat Bergson’s intellectual view of the metaphor. For Bachelard, «images would no longer occur simply to compensate the deficiencies of conceptual language. Images of life would be an integral part of life itself. One cannot know life better than in the production of its images» (ibid., p. 291). The “life” Bachelard refers to is that of «imagination as guide of human life», as the force of all human creativity.

Bachelard’s phenomenology of imagination views the image as the origin, not the product, of a new consciousness, restoring to language its autonomy: «The metaphor comes to give a concrete body to an impression difficult to express. But it is relative to a psychic being different from itself. The image, product of absolute imagination, takes its whole being from imagination» (Espace, p. 79). Bachelard’s insistence on the psychological purity of absolute imagination (hence the term “absolute”) is a reflection of his polemic position in favor of a phenomenology of imagination in his Poétique books, his last two monographs on imagination: «The poetic image illumines consciousness with such a light, that it is quite vain to seek unconscious antecedents for it» (Rêverie, p. 3). Bachelard’s phenomenological approach is not inconsistent with the view of language and other contents of consciousness as being relatively determined by psychological influences. Only his perspective is different. A phenomenological study of literary imagination seeks to understand the creativity of consciousness in its purity and autonomy. It is a method putting the possible antecedents of consciousness into brackets in order to examine the rules of imagination itself as creator of a new consciousness.

In point of fact, the metaphor can be studied phenomenologically by emphasizing its value as image, as a concrete perceptual image. To revivify the artificial or conventional metaphor of professors of rhetoric, says Bachelard, the laws of the imagination of matter must be introduced: «Living imagination is not content with comparisons. It is not satisfied with surface colors or a fragmentary form. It wants the totality of the image and the entire dynamics of the image» (Volonté, p. 245). Form is secondary to substantial depth and dynamism in the “living” image as metaphor: «And language contains the dialectic of the open and the closed. By meaning it encloses, by poetic expression it opens» (Espace, p. 199). Bachelard’s study of literary expression strips away the inert linguistic conventions of society (the realm of common “meaning”) in order to animate the individualizing power of the poetic image.

The most perfect manifestation of the poetic image is the literary image, which is «the liaison of the metaphor and the image», or the «pure literary image», which works only in literature (Air, p. 206). Bachelard’s method of analysis is not to reduce the realism of the metaphor to one of its two terms, but to consider the imaginative power of both: «Every metaphor contains in itself a power of reversibility; the two poles of a metaphor can alternately play the role of the ideal or the real. With these inversions, the most hackneyed expression like flight of oratory, comes to take on a little substance, a little real movement» (Air, p. 68). By reading metaphors literally in order to live their dynamic ontology, Bachelard violates the cardinal rule of objective literary criticism which respects stylistic context, the integrity of the literary work as a frame of reference in itself[29]. From the standpoint of a philosophy of imagination, however, Bachelard’s “subjectivism” restores the literary image to its autonomous function as creative experience.

The literary image should be the birth of a new meaning, rather than a resume of old ones. It is, of course, a polyvalent symbol, polysemantic in its simultaneous evocation of various denotations with their emotional values. But the true image renovates conventional metaphors: «A literary image destroys the lazy images of perception. Literary imagination disimagines to better reimagine» (Volonté, p. 26). Bachelard’s phenomenological method treats the image in its purest function as origin of consciousness: «there is no reality antecedent to the literary image. It does not come to clothe a naked image, nor to give speech to a mute image. Imagination speaks in us, our dreams speak, our thoughts speak. All human activity desires to speak» (Air, p. 283). The poetic image is the first exteriorization of imagination’s fundamental will to logos, man’s essential need of creativity as manifestation of his spirituality. Bachelard isolates the poetic image from other forms of causality in order to study it in its creative purity.

The pure poetic image, then, is «the subject of the verb “to imagine.” It is not its predicate» (ibid., p. 22). As origin, «the poetic image is a sudden relief in the psyche» (Espace, p. 1). It is «the most fugitive product of consciousness» (ibid., p. 4). «But the ephemeral image amasses so many values in an instant that one could very well say that it is the instant of the first actualization of a value. Thus we do not hesitate to say that imagination is a prime function of the human psyche» (Volonté, pp. 391-392). The values of psychic intentionality and of man’s spiritual need to create reality are constantly in the process of concretization. The poetic image solidifies the intentionality of dynamic imagination. For Bachelard, imagination and will are more fundamental than archetypes or perception: «The poetic image has a double reality: a psychic reality and a physical reality. It is by the image that the imagining being and the imagined being are closest. The human psyche is formulated primitively in images» (ibid., pp. 4-5). Negating the ultimate causality of psychological development, Bachelard affirms the freedom of imagination in the creation of mind.

We shall thus consider the poetic image as a theme of “direct ontology”. The poetic image, in this perspective «is not the echo of a past. On the contrary, through the burst of the image, the distant past reverberates with echoes, and one scarcely sees the depths in which they will resound and be extinguished. In its novelty, in its activity, the poetic image has its own being, a proper dynamism» (Espace, pp. 1-2)[30]. Rather than being a by-product of memory, the poetic image transcends these correlations between past and present. The pure poetic image transcends the temporality of language itself to reach a level of absolute creativity. Bachelard’s last two monographs on imagination emphasize phenomenology in order to reach man’s creative purity: «To specify that the image is before thought, one should say that poetry is, rather than a phenomenology of the mind, a phenomenology of the soul» (ibid., p. 4). Bachelard’s phenomenology of reverie and poetic creation hold the key to an ontology of poetry which is, at the same time, a phenomenology of imagination’s disclosure of the spirit.

- Poetic Reverie and Imaginative Creation

To conclude this essay we will describe the process of poetic reverie in order to define its central position in Bachelard’s ontology of imagination. Reverie is the creative daydream, experience (or images) perceived in a semiconscious state. The specifically poetic reverie is written; it animates written expression while the words coordinate it. Reverie is the state of consciousness which works in various forms of the imagination of matter, where unconscious forces confront perceptions and color them with personal affectivity. Here, on the other hand, we shall treat reverie as «a universe in emanation» (Eau, p. 11), the imagining consciousness as the origin of creativity. Reverie is the state in which the poetic image actualizes a new being of imagination. A phenomenology of poetic reverie should therefore illustrate «the fundamental role of imagination in all spiritual genesis» (Air, p. 193).

The difference between the sleeping dream and the reverie is essential, although Bachelard continually stresses the unity of the oneiric life: «Our oneiric being is one. It continues in the day itself the night experience» (ibid., p. 31)[31]. In reverie «the possible intervention of waking consciousness is the decisive sign» (Rêverie, p. 10). The element of volitional freedom clearly separates dream from reverie: «While the dreamer of a nocturnal dream is a shadow which has lost its I, the dreamer of reveries, if he is a bit of a philosopher, is able to formulate a cogito at the center of his dreaming-I. In other words, reverie is an oneiric activity in which a glimmer of consciousness subsists. The dreamer of reveries is present at his reverie» (ibid., p. 129). The sleeping dreamer has lost all conscious volition which could separate him, by a free choice, from the dreamed experience. The essence of reverie is thus found in relation to waking consciousness. Sleep is not the purest condition of imaginative creation: the imagining subject must be aware of his own creativity –as creativity.

The dreamer of reveries knows that it is he who originates the reverie. His imaginative solitude from outside experience is not complete. «His cogito which dreams immediately has, as the philosophers say, its cogitatum. Immediately, the reverie has an object, a simple object, friend and companion of the dreamer. In living from all reflections of poetry left to him by poets, the I which dreams the reverie discovers itself, not poet, but poetizing-I» (ibid., p. 22). Participating in an act of self-consciousness in imaginative creation, the dreamer of reveries is aware of himself as a creator (“poetizing-I”). This self-consciousness is the spiritual freedom of man in reverie.

Perception, Memory and Imagination. The same relations between the outside world of perception and the inside universe of imagination function in reverie as in imaginative reciprocity. Valorization of special substances corresponds to the stimulation of reveries, of inner experience, by important objects in the world, which are called “poetic pretexts”[32]. In that case, reverie remains «in the world, before the objects of the world. It amasses universe around an object, in an object» (Espace, p. 87). Just as with the imagination of matter and writing, the poetized object gives a certain coherence and homogeneity to the reverie of the dreamer. More often than not, however, the “poetic pretext” is a rationalization invented by the poet who «pretends to be attached to the real even when he is imagining» (Volonté, p. 231). It is therefore more relevant for a phenomenology of imagination to study reverie as a creative act, to render to «reverie its true freedom and its true function as creative mind» (Feu, p. 184)[33].

The relation of reverie to memory also reinforces the autonomy of imagination with regard to objective reality. For Bachelard, memory is grounded primarily upon imaginative, not perceptual, experiences. His analysis of esthetic contemplation in the genesis of meditation provides a context for the interaction of inner and of outer reality:

Astonishment is an instantaneous reverie. Then comes contemplation–strange power of the human soul capable of reviving its reveries in spite of the accidents of sensory life, of starting afresh its imaginative life. Contemplation unites more memories than sensations. It is more history than spectacle. When one believes to be contemplating a prodigiously rich spectacle, he is enriching it with the most diverse memories. Finally comes representation. It is then that imagination of form intervenes, with reflection on recognized and caressed forms, and with memory, this time faithful and well-defined (Air, p. 193).

Again, imagination precedes objective perception. The level of experience is set by the preliminary astonishment, which is a form of valorization, activating the intimate emotions of the beholder. Contemplation then is “enriched” with memories which are tinged with emotion and creativity («starting afresh its imaginative life»). Contemplation is a creative inwardness which takes the world as a companion. Finally – not primarily – the contemplator sees the world somewhat objectively in representation, according to the surface imagination of forms. Only after experiencing the rich depth of the spectacle – and at the same time his own depth –does the poetic spectator truly place himself in the world.

Memory revives old reveries because important memories have a value component as imaginative experience. Reverie is a technique of actually reliving our past: «The recalled past is not simply a past of perception. Already, since one remembers, the past is designated in reverie as a value of image. Imagination colors from the very beginning the pictures it likes to review. To return to the archives of memory, one must go beyond facts to regain values. Reveries are Impressionist paintings of our past» (Rêverie, pp. 89-90). The imaginative coloration of a remembered value is especially creative because the union of memory and reverie restores the ideal aspect of these first impressions. For example, «poetry gives us, not so much nostalgia for youth, which would be vulgar, but nostalgia for the expressions of youth. It offers us images as we should have imagined them in the “first impulse” of youth» (Espace, p. 47). The dead past of childhood, reimagined, remembered in terms of its reveries, becomes an ideal memory, and hence a «future of its living images, the future of reverie which is opened before every retrieved image» (Rêverie, p. 96). The union of memory and imagination within reverie can thus create a new being, transcending time and open to all possibilities[34].

Reverie and Ontological Reciprocity. The esthetic reciprocity of imaginative contemplation where the contemplated object (natura naturata) makes the spectator (natura naturans) an object of its consciousness, we have mentioned, is an extension into the world of the senses of an essentially internal process. In the final analysis, it is the absolute interdependence of subject and object within the state of reverie which gives this experience its ontological validity. Reverie is the model on which all imaginative relations of consciousness to its objects are ultimately judged.

Bachelard’s ontology of imaginative creation in reverie abolishes the separation between subject and object, the dualism which characterizes the conscious relation in the waking state. In reverie, the self-consciousness which does remain implies an ontology:

The cogito of the dreamer is less lively than the cogito of the thinker. The cogito of the dreamer is less certain than the cogito of the philosopher. The being of the dreamer is a diffuse being. But, on the other hand, that diffuse being is the being of a diffusion. It escapes the fixity of the hic et nunc. The being of the dreamer invades all that it touches, it diffuses in the world (ibid., p. 144).

Here the origin of the object is displaced from the objective world to the imagining consciousness of the subject who is «the being of a diffusion». The dreamer of reveries transforms the world from his own center of being. This passage continues by describing the absolute plenitude of being which such diffusion creates. The essence of imagination is precisely this power of absolute creativity, the demiurgic illusion which nourishes our «function of the unreal»:

Thanks to the shadows, the intermediary region which separates man and the world is a full region, and a plenitude of light density. That intermediary zone softens the dialectic of being and nonbeing. Imagination does not know nonbeing. The man of reverie lives by his reverie in a world homogeneous with his being, with his half-being. He is always in the space of a volume. Truly occupying all the volume of his space, the man of reverie is everywhere in his world, in an inside that has no outside. It is not for nothing that it is commonly said that the dreamer is plunged in his reverie. The world is no longer opposed to the world. In reverie, there is no more not-I. In reverie, the not no longer functions: all is welcome (loc. cit.).

The intermediary zone of reverie, while taking the world into account, is literally a world in itself. This absolute consubstantiality of subject and object in reverie («a world homogeneous with his being») since «there is no more not-I». Just as the poetic image is closest to the spiritual force of imaginative intentionality, in the realm of consciousness itself, «the man of reverie and the world of his reverie are closest, they touch each other, penetrate each other. They are on the same plane of being; if one must link the being of man to the being of the world, the cogito of reverie would be stated thus: I dream the world, therefore the world exists as I dream it» (ibid., p. 136). Bachelard’s reciprocal ontology of imagination ultimately makes man identical with the universe of which he is the creator[35].

Returning to Bachelard’s basic distinction between the real and the imaginative, we understand how man can conceive of an ideal state of being through imaginative creation. Poetry–for Bachelard, all the forces of esthetic will, projection and reverie –liberates us from passive adaptation to reality: «As soon as it is considered in its simplicity, one sees that reverie is the witness of a function of the unreal, normal function, useful function, which guards the human psyche, on the border of all the brutalities of a hostile not-I, of a not-I outsider» (ibid., p. 12). Imagination considered as autonomous in its own context («considered in its simplicity») is a negation of the real, a separation from the world of objective perception. Through his imaginative freedom of self-creation, man can become reconciled to an unresponsive outside world.

Autonomous in its essence, however, imagination does nourish waking life with great forces of esthetic projection, which is an extension of the “unreal” into reality. In this way, nature itself is enriched by the imagining consciousness to such a degree that it can, itself, solicit responses from the sensitive soul. This is the dialogue of esthetic reciprocity[36].

Now imagination is essentially a spiritual force, a function of becoming for the world and for the psyche. Man’s spiritual role is to feed imaginative being from within a closed universe in order to actualize his powers to love the real universe which, in turn, becomes his as he imagines its beauty. Bachelard’s spiritual philosophy of imagination is an optimistic message for man to exercise his intrinsic freedom, to transcend the world – and himself – by reconciling man and nature through the activity of imagination.

[1]For Bachelard as epistemologist see J. Hyppolite, L’épistémologie de G. Bachelard, in «Revue d’Histoire des Sciences», XVII, 1964, pp. 1-11; also G. Canguilhem, L’Histoire des sciences dans l’œuvre épistémologique de Gaston Bachelard, in «Annales de l’Université de Paris», 1, 1963, and Gaston Bachelard et les philosophes, in «Sciences», 24, 1963: reprinted in G. Canguilhem, Etudes d’Histoire et de Philosophie des Sciences, Vrin, Paris 1968, pp. 173-195; also P. Quillet, Bachelard, Seghers, Paris 1964. The most complete study of Bachelard’s epistemology as it parallels his theory of artistic creativity is the book of P. Ginestier, Pour connaitre la pensée de Bachelard, Bordas, Paris 1968.

[2] The following books of G. Bachelard have been quoted in this article. They are given in order of publication. All translations are mine. Abbreviations used in my text are given in parentheses: (Feu) La Psychanalyse du Feu, Gallimard, Paris 1938; (Eau) L’Eau et les Rêves, Essai sur l’imagination de la matière, Corti, Paris 1942; (Air) L’Air et les Songes, Essai sur l’imagination du mouvement, Corti, Paris 1943; (Volonté) La Terre et les Rêveries de la Volonté, Essai sur l’imagination des forces, Corti, Paris 1948; (Repos) La Terre et les Rêveries du Repos, Essai sur l’imagination de l’intimité, Corti, Paris 1948; (Espace) La Poétique de l’Espace, Presses Universitaires de France, Paris 1957; (Rêverie) La Poétique de la Rêverie, P.U.F., Paris 1960. Not cited are Lautréamont, Corti, Paris 1939 and 1965, and La Flamme d’une Chandelle, P.U.F., Paris 1961. Bibliography: «Revue internationale de Philosophie», 66, 1963, pp. 492-504; and in F. Pire, De l’Imagination Poétique dans l’oeuvre de Gaston Bachelard, Corti, Paris 1967, pp. 203-220. The latter work, published after the formulation of my own research, happily confirms my view of the primacy of dynamic imagination as a metaphysical principle for Bachelard. Now available in English translation are The Psychoanalysis of Fire, tr. A. Ross, Beacon Press, Boston 1964; The Poetics of Space, tr. M. Jolas, Orion Press, New York 1964; now Beacon paperback; The Poetics of Reverie, tr. D. Russell, Beacon Press, Boston 1969; and an anthology edited by C. Gaudin, On Poetic Imagination and Reverie, Bobbs Merrill, New York 1971.

[3] The following studies have been inspired by Bachelard’s emphasis on archetypes and the imagination of the four elements: G. Durand, Les Structures Anthropologiques de l’Imaginaire, Introduction à l’archétypologie génerale, P.U.F., Paris 1963, esp. his Introduction where Durand compares Bachelard’s theory of imagination with those of Bergson and Sartre (pp. 9-56); M. Mansuy, Gaston Bachelard et les Eléments, Corti, Paris 1967, which contains a useful “panorama” of Bachelard’s influence (pp. 353-380); H. Tuzet, Le Cosmos et l’Imagination, Corti, Paris 1965. The most complete and precise survey of Bachelard’s literary criticism is the outstanding Sorbonne thesis of V. Therrien, La Revolution de Gaston Bachelard en critique litteraire, ses fondements, ses techniques, sa portée, Klincksieck, Paris 1970, followed by an account of Bachelard’s intellectual itinerary, La Révolution humaniste de Gaston Bachelard; essai sur les fondements, la genèse, les structures d’une pensée (as yet unpublished).

[4] The use of imagination in psychotherapy was practiced by R. Desoille, Exploration, de l’affectivité subconsciente par la methode du rêve éveillé, Paris 1938 and Le rêve éveillé en psycothérapie, Paris 1945, both of which Bachelard discusses; cf. Air, pp. 14, 129-145; Volonté, pp. 392-394; Eau, p. 10-16; Repos, p. 82. Today similar work is being carried out by J. L. Singer, Daydreaming: An Introduction to the Experimental Study of Inner Experience, Random House, New York 1966, bibliog., pp. 215-225; also, Singer, The Vicissitudes of Imagery in Research and Clinical Use, in «Contemporary Psychoanalysis», 7, 2, Spring 1971, pp. 163-180.

[5] Cf. also Volonté, pp. 26, 27, 165; Air, p. 10; Eau, pp. 10, 23, 93-94, 140. (These and similar page references are for a further study of the issue at hand.)

[6] Cf. also Espace, pp. 111, 149; Repos, p. 302; Eau, pp. 86, 134.

[7] As early as Air, Bachelard despairs of the possibility of establishing a philosophy of autonomous imagination. The view of Bachelard as “evolving” from a psychoanalytical to a phenomenological analysis of imagination is thus erroneous. His earlier books simply emphasize the determinism of imagination while still pointing out its possible freedom.

[8] In 1938 Bachelard published two complementary monographs: La Psychanalyse du Feu and La Formation de l’esprit scientifique: Contribution à une psychanalyse de la connaissance objective. Feu, the first book devoted primarily to imagination, is still written from the point of view of a psychoanalysis of empirical knowledge, i.e., the study of imagination in order to abolish the “epistemological obstacles” it brings to scientific knowledge. In the present article, I mention the problem of scientific knowledge only in relation to imagination considered as a positive force.

[9] Bachelard describes this commitment of affectivity to a phenomenon as a “valorization” of the object. A perception which is experienced as a subjective value is the richness of human experience. Cf. below, and Feu, pp. 14, 44; Espace, p. 15; Air, p. 70.

[10] Cf. also Feu, p. 133 with regard to the creation of character in the novel; Volonté, pp. 130-131 concerning scientific research; also, Espace, p. 100; Repos, p. 47; Eau, p. 53.

[11] Cf. also Feu, pp. 23, 26; Repos, pp. 97-98, 214, 292-294.

[12] Cf. also Eau, pp. 20, 236; Volonté, p. 99; Air, p. 145.

[13] Cf. also Air, pp. 65, 158, 193. The relation of the imaginative elements to the imagination of matter will be studied below. The imagination of matter is subordinated to dynamic imagination; imagination is not the sum of its images, its material, but pure force, motion without matter.

[14] Cf. also Volonté, pp. 20, 27, 71; Eau, p. 117; Repos, p. 312; Espace, p. 4.

[15] Cf. Volonté, pp. 93, 98, 176, 362. This is perhaps the key to a philosophy of autonomous imagination.

[16] Cf. also Eau, pp. 157, 202, 205, 247; Air, pp. 13, 202; Volonté, p. 203; Repos, p. 81.

[17] “By this we wish to express that pancalist activity tends to transform every contemplation into an affirmation of universal beauty”, cf. J. M. Baldwin, Théorie génétique de la réalité, le pancalisme, tr. (Air, p. 61, note 23.) The original English edition is: J. M. Baldwin, Genetic Theory of Reality, being the outcome of genetic logic as issuing in the aesthetic theory of reality called pancalism, with an extended glossary of terms, G. P. Putnam’s Sons, New York and London 1915.

[18] Cf. also Volonté, pp. 8, 211; Repos, p. 29.

[19] Cf. also Volonté, p. 318; Eau, pp. 15, 37, 41-42; Air, p. 173; Repos, p. 98. See below “Metaphor and the Poetic Image” for the exact interpenetration of subject and object, and “Reverie and Ontological Reciprocity” for a phenomenological analysis of this relation.

[20] Cf. also Air, pp. 30, 58, 123, 141; Eau, pp. 93-94, 200.

[21] Cf. also Eau, pp. 2-3, 14-15, 31, 33, 70-71, 126, 144-148, 203, 224, 252; Volonté, pp. 32, 115, 233; Air, p. 137; Repos, pp. 4, 8-9, 51, 53-54; Feu, p. 94.

[22] It is thus that the schematization of the cherished substances in a poet’s imagery can reveal the orientation of his intimate concerns. To be true to the nature of imagination itself, however, this adjunct of archetypal or thematic criticism should seek the nuance and direction of a theme, its dynamism (see works of J. Hytier cited in note 32); also Eau, pp. 63-64, 79-80; Repos, p. 324; Air, p. 234.

[23] Analogous to the determinism of psychological complexes and archetypes, a consistent material imagery does suggest a limit to imaginative freedom. However, as indicated in the previous note, images of matter themselves constitute imagination only insofar as they are transformed by imagination as action.

[24] Cf. also Volonté, pp. 21-24, 32-33, 39-40, 53-56, 65; Eau, pp. 146-147, 214.

[25] Cf. also Air, pp. 14-17, 30, 88, 97, 110-111, 127, 290, 294, 296, 300; Volonté, pp. 199-200, 371; Repos, pp. 295, 303-304.

[26] Cf. also Espace, p. 17; Air, pp. 10, 13, 302; Volonté, p. 8.

[27] Cf. also Air, pp. 12, 279, 288; Espace, p. 7; Repos, pp. 12, 184, 312; Rêverie, pp. 3-4; Volonté, p. 76; Eau, p. 24.

[28] Cf. also Repos, pp. 82, 215; Eau, pp. 27, 253-254; Air, pp. 115-116, 272, 275, 284.

[29] For the theoretical foundations of modern stylistics see M. Riffaterre, Criteria for Style Analysis, in «Word», 15, 1, April 1959, and Stylistic Context, «Word», 16, 2, August 1960; reprinted in Essays on the Language of Literature, eds. Chatman and Levin, Houghton Mifflin Co., Boston 1967), pp. 412-441.

[30] Cf. also Rêverie, 47; Air, 19, 48, 62, 67, 286; Eau, 46-47, 116-117, 129, 163-164, 168; Espace, 3, 12, 20, 81, 144; Volonté, 3-6, 16, 71, 184-185, 382, 390; Feu, 117, 180-181; Repos, 144, 173-174, 262, 320.

[31] Cf. also Air, pp. 81, 84; Volonté, pp. 98, 218; Eau, p. 248. Bachelard’s insistence upon the influence of the unconscious (dream) life in waking experience is just another way of following the “continuous path from the imaginative to the real”. However, as we have stressed throughout, this psychological view is secondary to the problem of the autonomy of imagination which the ontological value of reverie here illustrates.

[32] Bachelard uses the term «pretext» in Feu, pp. 32, 146 and Espace, p. 143. Cf. J. Hytier, Les pretextes du plaisir poétique, in «Le Plaisir Poétique», Paris 1923, and his sequel, L’activité poétique et l’activité esthétique dans la poésie, in «Journal de Psychologie», 23, 1926, pp. 160-182 (reprinted in Les Arts de littérature, éditions Charlot, 1945). The latter article is essential in unifying Bachelard’s primitive correlations of reverie to the entire creation, composition and reading of a poem.

[33] This is the last sentence of the book, nevertheless written from a rationalistic standpoint. Cf. also Feu, p. 32; Eau, p. 182; Volonté, p. 383.

[34] Cf. also Espace, pp. 28, 33-34, 42, 65, 73, 117; Rêverie, pp. 18, 100, 118-119.

[35] Cf. also Rêverie, pp. 131, 150; Air, pp. 54, 142, 194, 229-230; Repos, pp. 98, 199; Espace, p. 4.

[36] This notion of reciprocity has been developed by M. Dufrenne in Phénoménologie de l’expérience esthétique, 2 vols., P.U.F., Paris 1953; in Le Poétique, P.U.F., Paris 1963, Dufrenne gives primacy to Nature in molding the poetic perception of man.